Speed's effect on air resistance

There is a worldwide hunt in the search for options to optimize running performance through reducing the air-resistance among runners, coaches and running scientists.

Cyclists and speed-skaters have been doing this for a long time already by developing optimal aerodynamic conditions (clothing, frames, body position, streamlining, drafting).

In running, there have been a few breakthroughs in capturing air resistance recently. The first came with the development of the new Stryd, which reports the Air Power in real time. The second was the sensational INEOS 1:59 Challenge. In Vienna, Eliud Kipchoge was helped by 41 pacers (5 teams of 7 pacers and 6 reserves) to achieve his magnificent 1:59:40.

This paper will focus on an earlier (and spectacular) demonstration of the impact of the air-resistance. Back in 2011 American sprinter Justin Gatlin ran the 100 meters in a sensational time of 9.45. He managed to do this during a special race organized by the Japanese TV-show Kasupe! They had arranged that he was assisted by a tailwind provided by huge fans (capable of blowing wind at 32 km/h)!

Consequently, Gatlin ran faster than the present-day world record of Usain Bolt (9.58), although he had never run faster than 9.95 seconds in regular races in the 2011 season. Apparently, the tailwind gave him a net advantage of no less than 0.5 seconds!

In this paper, we will calculate how high advantage in the air-resistance has been to see whether we can explain the result.

Theory

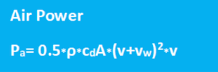

In our book ‘The Secret of Running’, we have discussed the theory of the air-resistance in various chapters. According to the fundamental laws of physics, the power required to surmount the air resistance Pa (Air Power) is determined by the density of the air ρ (in kg/m3) the air-resistance factor cdA (in m2), the running speed v (in m/s) and the wind speed vw (in m/s), as shown in the box.

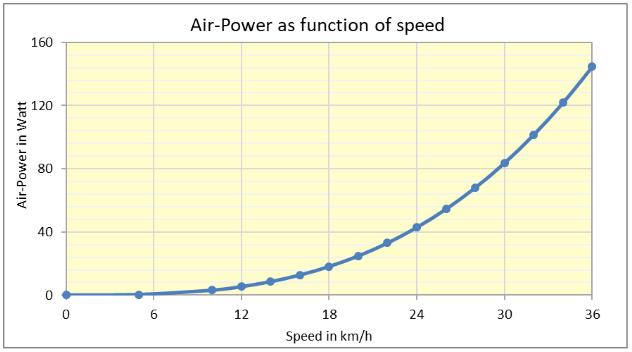

The figure below shows the Air Power as a function of running speed v at the standard conditions (temperature 20°C, air-pressure 1013 mbar, so ρ = 1.205 kg/m3, cdA = 0.24 m2, no wind, so vw = 0 m/s). At Gatlin’s speed (38.1 km/h) the Air Power at the standard conditions equals a staggering 171 Watts.

How big was the advantage of the tailwind?

This question cannot be easily answered as we do not know exactly how high the wind speed was. YouTube tells us that the speed in the fans was 32 km/h, but a large part of this wind will have been lost to the ambient air. It seems obvious that the real tailwind that Gatlin experienced will have been much lower.

We have estimated this real tailwind by using the power balance: Pt = Pa + Pr. So, we have assumed that the total power Pt of Gatlin remained the same. Without tailwind, this power enabled him to run 9.95, with tailwind the same power enabled him to run 9.45.

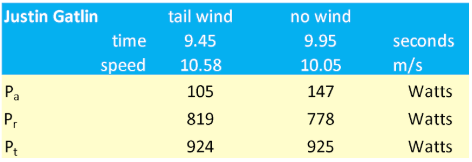

In the case without tail wind, his speed was 10.05 m/s, so his Pr must have been 10.05 * 79 * 0.98 = 778 watts (body weight 79 kg and ECOR 0.98 kJ/kg/km). At this speed his Pa was equal to 147 Watt, so apparently his Pt was 925 Watts.

In the case with tailwind, his speed was higher (10.58 m/s). Consequently, his Pr was 819 watts which is 41 watts higher than in the case without wind. So, we conclude that the air-resistance must have been 41 watts lower as a result of the tailwind.

Next, we have used the formula above to calculate at which wind speed the air-resistance would be reduced by 41 watts. This results in a tailwind speed of 5.8 km/h or only 18% of the speed of the fans. The results are summarized in the table below.

We note that this is a simplified calculation as we have neglected the power required for the acceleration in the first part of the race. Sprinters use a significant part of their power for this acceleration, as we have shown in our book ‘The Secret of Running’. As Gatlin obtained a higher speed with the tailwind, this means that he also will have used somewhat more power for the acceleration. When we taken this into account, the real tailwind speed will be higher than the above calculated 18%.

How fast could Justin Gatlin have run without any air-resistance?

This can be easily calculated as in this case Pa is equal to 0. This situation could occur when running on a treadmill or in a long wind tunnel with an air speed of slightly more than 10 m/s. In such cases Gatlin could use his total running power of 925 watts for the running resistance Pr.

The result thus becomes a speed of 925 / 79 / 0.98 = 11.95 m/s or a 100 meters time of 8.4 seconds! This calculation is also simplified as we did not take into account the power required for the acceleration in the first part of the race.

In our book ‘The Secret of Running’ we have calculated a similar time for Usain Bolt. On the one hand his Pt is larger than that of Gatlin and he was thus faster in normal races. On the other hand Bolt was heavier, so the air-resistance was relatively smaller in his case. The formula shows that the air-resistance is independent of the body weight, which means heavy runners have a small advantage.

Author Hans (who is a lightweight of 58 kg) has experienced this in cases of a strong head wind, when he was dropped from a pack of runners of similar quality.

If you would like to purchase The Secret of Running (or the German version, Das Geheimnis des Laufens), you can do so at the bottom of store.stryd.com.