Weight (Mass) and Speed: What You Need to Know

If you want to make progress and sharpen your PR at your favorite distance, introducing variation in your training is important. Are you a runner who often runs the same distance at the same pace? Introducing variation in your training will make a big difference. More on that later.

First, we want to talk about weight.

If you’re starting a few pounds overweight, losing that extra weight is the fastest way to progress. If you are (for example) twenty pounds heavier than is healthy for your height, you can, of course, train for a PR focused on power. That works, but it’s a bit like buying a new house because your windows are dirty. It works, but there’s an easier way. Note that we will use mass extensively in the next section rather than weight, but, assuming you are running on earth and not with some other planet’s gravity, which one we use does not matter much.

In The Secret of Running Hans and Ron write extensively about the relationship between weight and speed. They’ve devoted an entire chapter to it: How Much Faster Will You Go When You Lose Weight?

How big is the effect of your mass?

The mathematics of mass influence can be explained simply, according to Hans and Ron. Your body basically has a fixed power, P, in watts. If you run on a flat course, you use that ability to overcome running resistance and air resistance. If you lose a few pounds, your power remains constant (because your strength is unchanged), but your running resistance decreases. Result: you can run faster.

There is, however, a limit. Things go wrong at the point where you no longer lose excess fat, but muscle mass. We want to prevent runners from going overboard in their drive to lose weight. The moment your sweat starts to smell like ammonia, it’s important to start eating more. But again, knowing you can lose some of your extra pounds is an easy way to boost your speed. Overall, you can say that for every excess percent that you become lighter, you also become one percent faster. This makes sense, because you use less energy when you are lighter, while your heart-lung system is unchanged.

Note: this is a simplified explanation. It does not take into account certain physiological complexities, but generally applies to situations where excess weight is being lost.

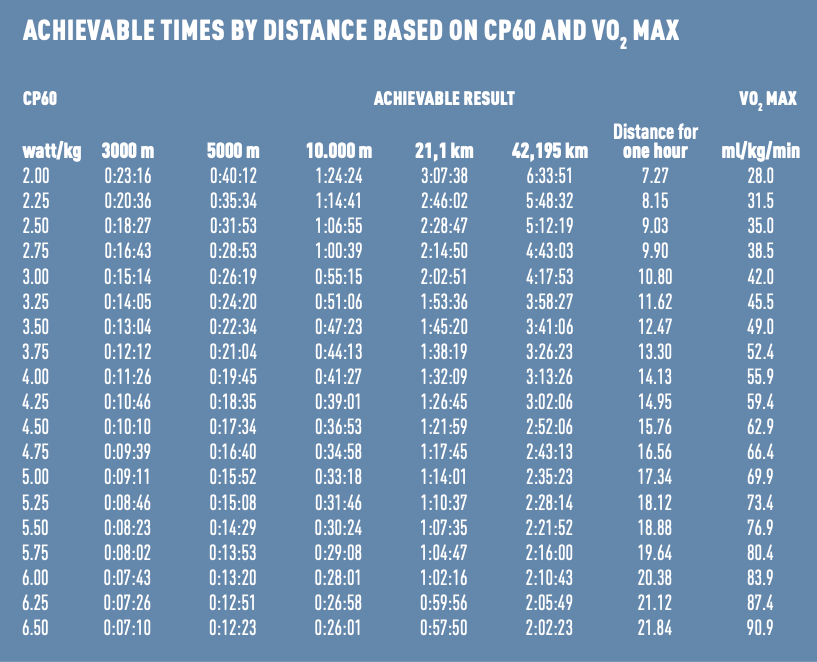

For this reason, your Critical Power (just like your tipping point) only becomes interesting when you start looking at your capacity per kilogram of body mass. So, a Critical Power of 250 Watts doesn’t say anything about your possible run times. If your mass is 60 kilos (a weight of 132 lbs), your power per kilogram of body mass is 4.1, but at a mass of 80 kilos (a weight of 178 lbs), your power per kilogram body mass is 3.1. For example, a 10 kilometer run with a Critical Power of 4.1 per kilogram of body mass takes around 41 minutes. The same run with a power of 3.1 per kilogram of body weight takes around 54 minutes. So, your power per kilogram of body weight is what matters, not your absolute power.

In the table above, you can see your favorite distance and your potential times at your current watt / kg. If the numbers start to make you dizzy, don’t panic. For runners who already run with Stryd, the Critical Power per kg isn’t rocket science. After all, you can easily go to your settings in the app and look at your Critical Power. You will then automatically see your capacity in W / kg. If this book is your first introduction to running with power, then you should remember: if you lose 1% excess weight, you will run 1% faster.

Not just theory

The above statements and figures have not only been studied theoretically, but have also been proven in practice in people who have lost excess weight. For example, Hans weighed 127 pounds in 1980 (with a height of 5’7”). More than thirty years later, he’d gained twenty pounds. With a targeted diet, Hans returned to his old weight of 57.5 kg (127 pound) in six months, a decrease of 15% in weight. His performance at all distances increased spectacularly during that period. In the end - you guessed it - Hans became 15% (!) faster on all distances.

Note: This is a personal anecdote; the effort to lose weight and the cost of losing too much weight vary across sex and age - please consult your doctor if you are not sure about your personal case!

Important: All of these situations only apply when someone has extra weight to lose. It can be dangerous to restrict your eating too much to hit a given weight. In this chapter, we’re referring to runners who have a few pounds more than they should - not runners who are already at a healthy weight.

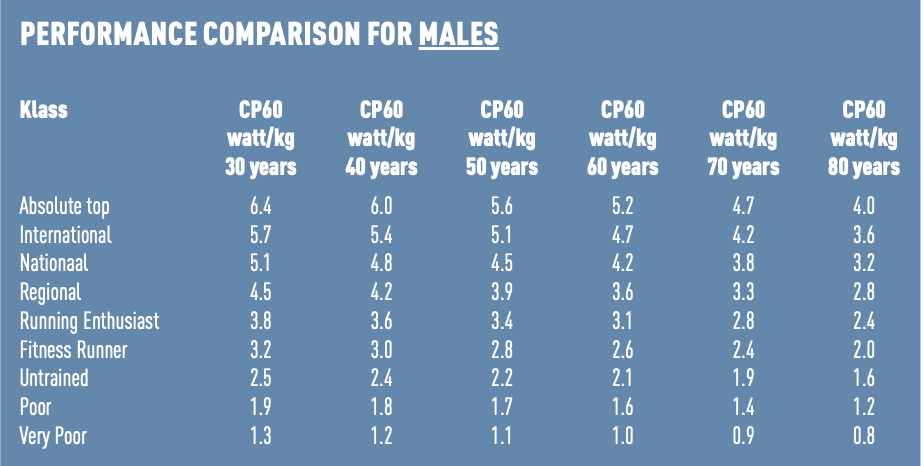

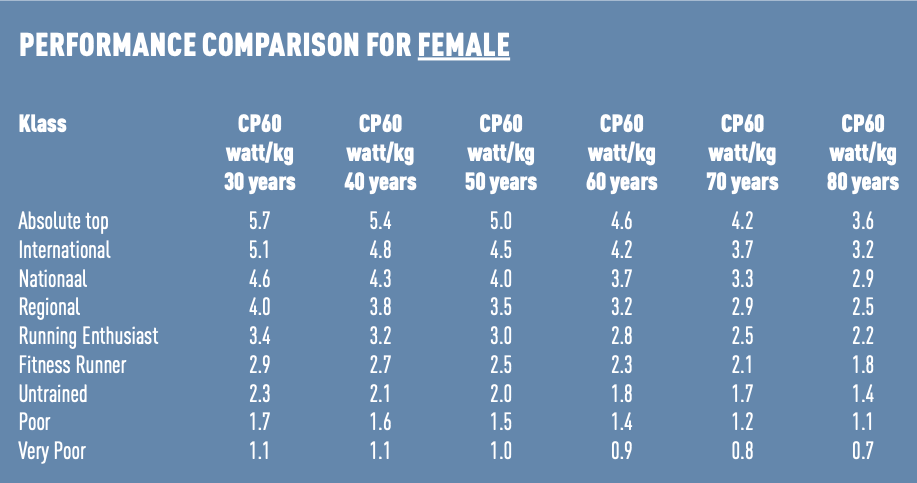

In addition to weight/mass, age also influences your running times. For example, if your Critical Power is 3.8 watts / kg, it makes a big difference in competitions whether you are 32 years old or 72 years old. As a 32-year-old, a Critical Power of 3.8 watts / kg is an excellent value, but you won’t find yourself at the top of performers for your age. However, if you’re 72 years old and are still running at 3.8 watts / kg, you will find yourself alongside the very best in your age. Hans and Ron made a nice overview of the levels per age category for women and men.

Want to learn more about Running Power?

Download The Fastest Way To Your Next Personal Best: Running Power eBook (with over 65+ pages of content) for free to learn simple ways you can use power to improve your running performance.

Click here to download. Enjoy the book!